'Be

Kind to Efts'

A

Model For Studying Environmental Problems, Issues and Challenges

As a boy Charles Kingsley became facinated by freshwater biology whilst living

on the

edge of the East Anglian fenland. Later in life he was part of a social network of scientists

and environmental reformers centred on the Bunbury family of Great Barton.

When he was 12

years old, he xperienced violent social unrest first-hand in the Bristol riots of

1831, and until his death in 1875, was deeply involved with the social and environmental

ferment of industrial development. One way or another, between the 30's and the 70's, he

became associated with all major political and social reform movements of the age of steam.

Kingsley's life coincided with the first historical period when primary evidence for future

historians accumulated at an unprecedented rate. He moved within, and between, the circles of

Royalty, the aristocracy, the church, business, and science. We can enter this world of

technological change and social ferment through his novels, sermons and letters, and cross-

reference to contemporary evidence about the lives of his friends and enemies. We can 'view'

Kingsley from the writings of others, and study the events, and 'visit' the places and social

movements which moulded his thoughts about families and the environment.

Charles Kingsley

was a crusader for environmental health reform, with a deep knowledge of

what we now call the ecological principles which create and maintain local biodiversity. In the

following poem Kingsley attempts to equate the interdependence of living things in ecosystems

with a Christian ethic of self-sacrifice. He imagined that the 'crowning glory of bio-geology',

when fully worked out, might, after all, only be 'the lesson of Christmas-tide- of the infinite self-

sacrifice of God for man'.

The

oak, ennobled by the shipwright's axe-

The

soil, which yields its marrow to the flower-

The

flower, which feeds a thousand velvet worms

Born

only to be prey to every bird-

All

spend themselves on others: and shall man,

Whose

two-fold being is the mystic knot

Which

couples earth with heaven, doubly bound,

His

being both worm and angel, to that service

By

which both worms and angels hold their life,

Shall

he, whose every breath is debt on debt,

Refuse,

forsooth, to be what God has made him ?

Only someone who

had actually felt the touch of earthworms could have written this.

Kingsley particularly

promoted the use of religious imagery based onnature, to carry notional

messages to communicate his concept ofGod.

On his return from

a holiday in the tropics to his Chester deanery, Kingsley married his recent

experience of walking the forest floor with spiritual readings of stone pillars and vaults as

follows.

"Now,

it befell me that, fresh from the Tropic forests, and with their forms hanging always, as it were, in

the background of my eye, I was impressed more and more vividly the longer I looked, with the likeness

of those forest forms to the forms of our own Cathedral of Chester. The grand and graceful Chapter-

house transformed itself into one of those green bowers, which, once seen, and never to be seen again,

make one at once richer and poorer for the rest of life. The fans of groining sprang from the short

columns, just as do the feathered boughs of the far more beautiful Maximiliana palm, and just of the

same size and shape: and met overhead, as I have seen them meet, in aisles longer by far than our

cathedral nave. The free upright shafts, which give such strength, and yet such lightness, to the

mullions of each window, pierced upward through those curving lines, as do the stems of young trees

through the fronds of palm; and, like them, carried the eye and the fancy up into the infinite, and

took

off a sense of oppression and captivity which the weight of the roof might have produced. In the nave,

in the choir the same vision of the Tropic forest haunted me. The fluted columns not only resembled,

but seemed copied from the fluted stems beneath which I had ridden in the primeval woods; their

bases, their capitals, seemed copied from the bulgings at the collar of the root, and at the spring

of the

boughs, produced by a check of the redundant sap; and were garlanded often enough like the capitals

of the columns, with delicate tracery of parasite leaves and flowers; the mouldings of the arches

seemed copied from the parallel bundles of the curving bamboo shoots; and even the fatter roof of the

nave and transepts had its antitype in that highest level of the forest aisles, where the trees, having

climbed at last to the lightfood which they seek, care no longer to grow upward, but spread out in huge

limbs, almost horizontal, reminding the eye of the four-centred arch which marks the period of

Perpendicular Gothic".

"He is the

God of nature, as well as the God of grace. For ever He looks down on all things

which He has made: and behold, they are very good. And, therefore, we dare offer to Him, in

our churches, the most perfect works of naturalistic art, and shape them into copies of

whatever beauty He has shown us, in man or woman, in cave or mountain peak, in tree or

flower, even in bird or butterfly.

But Himself ?-Who

can see Him ? Except the humble and the contrite heart, to whom He

reveals Himself as a Spirit to be worshipped in spirit and in truth, and not in bread, nor wood,

nor stone, nor gold, nor quintessential diamond".

Apart from offering

a personalised view of an important period, which witnessed the dawn of

mass production and a greatly increased pace of world development, Kingsley's writings ring-

true today because he was a social reformer who viewed society as a system driven by

interacting processes which integrate 'community and production'. He was a polymath with a

wide ranging grasp of the connections between scientific discovery, industrial development,

social well-being, and environmental well-being.

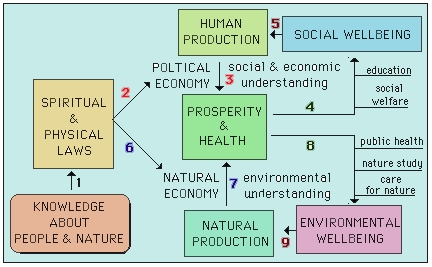

The following conceptual

map describes a system of human development through the

application of science. In sequence its dynamics may be traced by clicking on the numbers.

The Kingsleyan

System for social action to cure the ills of unchecked industrialism

.

.Knowledge about

the interactions of people with the workings of nature is accumulated by

thought, observation and experiment. This knowledge is organised in the form of physical laws

which explain the way nature works; and spiritual/ethical laws which define the ways we should

behave towards other people and the rest of nature.

Spiritual and ethical

laws are studied and applied to manage human production (the subject of

political economy) : i.e. political economy defines the way people are governed in their

everyday lives through political and economic understanding.

Improvements in

political and economic understanding are applied through social welfare and

education to increase social well-being.

Increased social

well-being stabilises human production.

Physical laws are

applied to manage natural production (the subject of natural economy) i.e.

natural economy defines the way people process physical and biological materials to meet their

needs and wants through environmental understanding.

Together political

and natural economy make up the subject of consumermatics, the body of

knowledge which defines the forces of consumerism which since Kingsley's day have

determined the pace of world development.

Improvements in

environmental understanding are applied through public health, nature study,

and care for nature, to increase environmental well-being.

Increased environmental

well-being stabilises natural production.

Unfortunately his

efforts, together with those of some of his contemporaries, notably John

Ruskin, to encourage the growth of an embryonic generalist education system, which covered

this holistic perspective, were swamped by the national priority for the training of specialists to

control nature and exploit an Empire. Kingsley's contemporary, Henslow, a Cambridge

professor began this process in his village school by getting pupils to dissect flowers and learn

scientific terminology. They helped Darwin in his botanical experiments. The impact of these

revolutionary ideas at the start of state support for education certainly turned the heads of the

inspectorate towards single-subject teaching.

In contrast, Kingsley's

starting point was the study of 'civilisation'.

"...give

me the political economist, the sanitary reformer, the engineer; and take your saints and virgins,

relics and miracles. The spinning-jenny and the railroad, Cunard's liners and the electric telegraph,

are

to me, if not to you, signs that we are, on some points at least, in harmony with the universe; ".

In this broader

context Kingsley offers an educational model for modern times where we

require a broad view of society and environment to absorb the educational implications of

sustainable development.

The period of Kingsley's

life was a triumph of invention and applied science which brought

about great changes in the appearance of the British countryside. In the main, these changes

were results of applied science, first to allow mass transport of people, and then to promote the

spread of new ideas through mass communication. Kingsley described science as a 'good fairy'

which could increase human well-being, providing it was harnessed to a political system which

aspired to develop the latent potential in everyone.

It is convenient

to define this period of rapid socio-environmental change as the 72 years

spanning the opening of the first public railway line in 1825 to the first experiments in wireless in

1897. People born in the first decade of the 19th century would have experienced the benefits

of mass production of goods and services in the 'age of steam', and from the launch of the

penny post in 1840, would have been able to respond to overnight news about people and

events throughout the world. They might have used the first public telephone exchange in 1878,

and seen the first motor cars in the 1880s. A person born in 1825 might have lived into their

seventh decade to celebrate Queen Victoria's Jubilee in 1897, the year in which the first plastic

records entered people's homes. Kingsley saw the early benefits of applied science but died

prematurely in 1875. He lived long enough however to become intensely aware of the human

and environmental disbenefits of unchecked industrialism organised for maximum profit, and the

social disfigurement it caused through substandard housing of urban workers .

Kingsley was one

of the first to value nature study as a worthwhile hobby. He was an amateur

sea-shore ecologist, and in the Water Babies he used the cleansing power of detritus feeders in

rock pool food chains as a metaphor to preach the need for proper waste management.

"Only

where men are wasteful and dirty, and let sewers run into the sea, instead of putting the stuff

upon the fields like thrifty reasonable souls; or throw herrings' heads, and dead dog-fish, or any other

refuse, into the water; or in any way make a mess upon the clean shore, there the water-babies will

not

come, sometimes not for hundreds of years (for they cannot abide anything smelly or foul): but leave

the sea anemones and the crabs to clear away everything, till the good tidy sea has covered up all the

dirt in soft mud and clean sand, where the water-babies can plant live cockles and whelks and razor

shells and sea- cucumbers and golden-combs, and make a pretty live garden again, after man's dirt is

cleared away. And that, I suppose, is the reason why there are no waterbabies at any watering-place

which I have ever seen".

The notion of conserving

living resources, from rare species to valued landscapes, means

managing their use so that vital stocks of plants, and animals are maintained for the benefit of

succeeding generations. But progress in educating for sustainable development has been

lamentably slow, largely because it has been seen as peripheral, and sometimes as a hindrance,

to humankind's continuing quest for social and economic welfare.

From the building

of the first coal-powered factories and mines a century before Kingsley, it

was clear that unchecked industrial enterprise is incompatible with nature. Linnaeus, for

example, on his Royal fact finding tour of Sweden's natural resources in the late 18th century,

reported on the poisonous fumes from copper smelters which had destroyed vegetation down-

wind of the factories. However, it was not until the middle of the next century that

commentators began to agitate for something to be done about the environmental impact of a

rapidly developing industrial society. John Ruskin, for example, railed against the ugly impact of

tourism on Europe's mountain landscapes. This was exacerbated by the pollution from holiday

resorts, which even then had begun to defile Alpine streams. Charles Kingsley summarised his

two-pronged attack on the socio-environmental effects of industrialism in a sermon preached in

1870 when he spoke of 'human soot' as a by- product of competitive investment in mass-

production.

"Capital

is accumulated more rapidly by wasting a certain amount of human life, human health, human

intellect, human morals, by producing and throwing away a regular percentage of human soot-of that

thinking and acting dirt which lies about, and, alas ! breeds and perpetuates itself in foul alleys

and low

public-houses, and all and any of the dark places of the earth.

But

as in the case of the manufacturers, the Nemesis comes swift and sure. As the foul vapours of the

mine and manufactory destroy vegetation and injure health, so does the Nemesis fall on the world of

man-so does that human soot, those human poison gases, infect the whole society which has allowed

them to fester under its feet. Sad; but not hopeless. Dark; but not without a gleam of light on the

horizon."

Kingsley was also

prophetic in his vision of more enlightened times when society would

demand that the countryside and human lives wasted by industrial development should be

cleaned-up.

"I

can yet conceive a time when, by improved chemical science, every foul vapour which now escapes

from the chimney of a manufactory, polluting the air, destroying the vegetation, shall be seized, utilised,

converted into some profitable substance, till the Black Country shall be black no longer, and the

streams once more run crystal clear, the trees be once more luxuriant, and the desert which man has

created in his haste and greed, shall, in literal fact, once more blossom as the rose.

And

just so can I conceive a time when, by a higher civilisation, founded on political economy, more

truly scientific, because more truly according to the will of God, our human refuse shall be utilised

like

our material refuse, when man as man, even down to the weakest and most ignorant, shall be found to

be (as he really is) so valuable that it will be worth while to preserve his health, to the level of

his

capabilities, to save him alive, body, intellect, and character, at any cost; because men will see that

a

man is, after all, the most precious and useful thing in the earth, and that no cost spent on the

development of human beings can possibly be thrown away".

The growing conflicts

between economic development and quality of environment took more

than a century to come to a head in the Rio Environment Summit. This assembly of world

leaders in 1992 highlighted a global imperative to promote inter- disciplinary systems thinking,

and encourage communities to express their concerns about quality of life in local environmental

action plans. In the context of modern environmentalism, the world of Charles Kingsley is an

exemplar for constructing appropriate holistic knowledge maps about the connections between

the technical, biological and spiritual components of sustainable development. He was one of

the first people to offer an overview of world development that took account of applied

science, its detrimental social and environmental impacts, and the need to consider the spiritual

dimensions of 'place' and 'change'. His novels are imaginative and popular interpretations of his

ideas presented on various stages, some of which were contemporary, and others were set in

more exotic places and distant times. His messages were the same: to urge government to

action, and to calm social strife through the 'eternal goodness' of religion.

"And now, my dear little man, what should

we learn from this parable?

We

should learn thirty-seven or thirty-nine things, I am not exactly sure which: but one thing, at

least, we may learn and that is this-when we see efts in the ponds, never to throw stones at them, or

catch them with crooked pins, or put them into vivariums with sticklebacks, that the sticklebacks

may prick them in their poor little stomachs, and make them jump out of the glass into somebody's

workbox, and so come to a bad end. For these efts are nothing else but the water babies who are

stupid and dirty, and will not learn their lessons and keep themselves clean; and, therefore (as

comparative anatomists will tell you fifty years hence, though they are not learned enough to tell

you now), their skulls grow flat, their jaws grow out, and their brains grow small, and their tails

grow

long, and they lose all their ribs (which I am sure you would not like to do), and their skins grow

dirty and spotted, and they never get into the clear rivers, much less into the great wide sea, but

hang about in dirty ponds, and live in the mud, and eat worms, as they deserve to do.

But

that is no reason why you should ill-use them: but only why you should pity them, and be kind

to them, and hope that some day they will wake up, and be ashamed of their nasty, dirty, lazy,

stupid life, and try to amend, and become something better once more. For, perhaps, if they do so,

then after 379,423 years, nine months, thirteen days, two hours, and twenty-one minutes (for aught

that appears to the contrary), if they work very hard and wash very hard all that time, their brains

may grow bigger, and their jaws grow smaller, and their ribs come back, and their tails wither off,

and they will turn into water-babies again, and, perhaps, after that into land-babies; and after that,

perhaps, into grown men.

You

know they won't? Very well, I dare say you know best. But, you see, some folks have a great

liking for those poor little efts. They never did anybody any harm, or could if they tried; and their

only fault is, that they do no good-any more than some thousands of their betters. But what with

ducks, and what with pike, and what with sticklebacks, and what with water-beetles, and what with

naughty boys, they are 'sae sair haddened doun', as the Scotsmen say, that it is a wonder how they

live; and some folks can't help hoping that they may have another chance, to make things fair and

even, somewhere, somewhen, somehow."